Chapter 7

Three Dimensional Modeling -The Spreadsheet

Documentation

This spreadsheet is, in the main, a large macro written in the Visual Basic language.

Rather than describe the spreadsheet in Visual Basic terms, the writers have chosen

to employ a largely mathematical description.

The applications of the worksheets are to determine trajectories in three dimensions for orbiting (and sub-orbiting) objects. Newton’s inverse square law of gravitational

attraction, buoyancy and atmospheric resistance are accounted for in the equations.

The coordinate system is xyz. The origin is such that the central body being orbited is assumed to be spherical with its centre fixed at the origin of the xyz system

with the z-axis emerging from the north pole of the sphere. The xyz coordinates are absolutely fixed with respect to the universe.

In the case of the Earth, the central body rotates on its axis once per sidereal day. A point located on or near Earth is specified by fixed Latitude, Longitude, and Altitude coordinates. In terms of the xyz coordinate system, points attached

to Earth have their xy coordinates constantly changing due to rotation about the z-axis.

The atmosphere is assumed to rotate with the Earth.

The model is set up such that the launch point is in the xz plane at t = 0 (the time of launch), irrespective of where the point is located on Earth.

Worksheets

There are four worksheets, Paris, Geo, Elliptic, and Planet,

each intended for

different modeling situations.

Paris

This sheet is intended for sub-orbits near Earth where atmosphere resistance is

at play. Inputs include the location of the launch point. Outputs include the impact

point and its range and bearing from the launch point. It is assumed that the launcher

is fixed to the earth.

Geo

Used to study geosynchronous orbits that are strictly along the equator

of the body being orbited.

Elliptic

Used to study arbitrary orbits.

Planet

Intended for use in determining the trajectory for any planet. A site that provides

data for planet orbits can be seen here.

Charts of orbits are the orbits projected on the xy plane. Highly inclined

orbits will usually look artificially elliptical.

Input Parameters

The same set of parameters, more or less, is provided for all the sheets. The exact

set of parameters, their interpretation and wording, changes from sheet to sheet.

Latitude, Longitude, and Altitude are Earth based coordinates of a launch point.

For a satellite launch, Latitude and Longitude are values projected down to earth's

sea level.

See the following parameters for the Elliptic sheet as an example.

Latitude

This is the latitude, in degrees, of the launch point as measured on the earth.

On the planet sheet this parameter is used to specify the initial location above/below

the orbit plane that the planet has at t = 0. For satellites on the Geo sheet, Latitude

is forced to 0.

Longitude

This is the longitude, in degrees, of the launch point as measured on the earth.

East is positive and West is negative. The launch point is always aligned

with the xz plane at t = 0.

Altitude

On the Planet sheet, this parameter is Distance and represents the centre-to-centre

distance between the sun and the planet. For the other sheets, this is the altitude

of the launch point. Altitude is zero at sea level on earth.

At time t = 0 a launch point is in the xz plane so the initial x, y, z, r, θ, φ

of the object are:

r = earthRadius + Altitude

θ = 90 - Latitude (degrees)

φ = 0

x = (earthRadius + Altitude) * cos(Latitude)

y = 0

z = (earthRadius + Altitude) * sin(Latitude)

Elevation

This is the launch point elevation in degrees, the angle above the local

horizontal or tangent plane that the launch barrel is pointing. The meaning

is similar for satellite launches; elevation is zero if the object is launched in

the tangent plane. For satellites on the Geo sheet elevation is forced to

zero.

Azimuth

This is the number of degrees from north the launch barrel is pointed, as measured in the

tangent plane. On Earth this would be called the compass bearing. East

is 90 degrees and so on.

Launch Velocity

This is the initial velocity of the object in meters per second. For a cannon or other

launch device attached

to the Earth, the Earth's spin on the z-axis imparts an easterly velocity to any launched

object. The appropriate velocity is provided by the software as determined from

the latitude of the launch site.

After launch, the object is subjected to the same orbital

physics as are satellites and planets. The velocity of an orbiting object is measured

with respect to the xyz coordinate system. Except for the Paris sheet, the launch is assumed to occur from a platform that is stationary with respect to the

xyz coordinates.

G*M

The Standard Gravitational Parameter.

For Earth G*M ~= 398,600,441,800,000 metres^3/second^2.

For our Sun G*M ~= 132,712,440,018,000,000,000 metres^3/second^2.

Sidereal Day

This is the rotation period of the Earth in seconds, not used on the Planet sheet. It is

used to calculate the longitude of an object at a given time. The longitude is needed

to calculate the arc distance and bearing from launch point to object. If

the objects coordinates are x, y, z then:

Object_r = sqrt(x^2 + y^2 +z^2)

Object_θ =atan(z / r)

Object_φ =atan(y / x)

Since φ corresponds to Longitude and φ = 0 for the launch point at t = 0, then

at time t

Launch_φ = (2 * π * t) / SiderialDay

The Longitude of the object at any t, x, y, z, is:

Object_Longitude = atan(y / x) - (2 * π * t ) / SiderialDay + Longitude

Also, Object_Latitude = π / 2 - Object_θ

= π / 2 - atan(z / r)

Rotation Factor

The value zero turns off earth's rotation, the value one turns it on. This could

be used to demonstrate the effect of Coriolis.

Earth Radius

We usually employ a radius of 6,371,010.00 metres.

Object Density, Object Radius, Cd

These parameters are the same as described in Chapter 3 and Chapter 6. For a discussion

of Cd, see Chapter 6 "The Drag Coefficient".

In Chapter 3 we took buoyancy into account as a modification to g in the differential

equation. That was because buoyancy creates a force that is opposite to gravity:

One may think of an effective or buoyant mass mb for an object with mass m where:

mb = m * (1 - pfluid / pobject). Under gravity the object will fall if its density

is greater than that of the fluid and rise if less.

Step Size

This is the integration interval in seconds.

Steps Per Output

This is the number of integration steps from one output row to the next. Use 1 to

get one output for each integration step.

Number of Outputs

This is the total number of rows of output. If Outputs were 1,000 and Steps were 1,000 then

there would be 1,000,000 integration steps.

Last Output Time

The value in this cell is Step size * Steps Per Output * Number of Outputs.

Area, Volume, Mass, k Sea Level

These are the same as in previous topics.

Obs Latitude

On the Elliptic sheet. This is the latitude of an observer on earth, in degrees.

North is positive.

Obs Longitude

On the Elliptic sheet. This is the longitude of an observer on earth, in degrees.

East is positive.

Analytic Outputs

These are seen in column D and were described in the preceding topic.

The Output Table

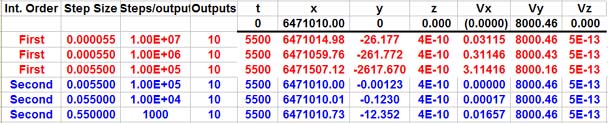

Some rows from the output table for the Elliptic sheet are shown next, in two sections.

The output needs of the four sheets differ, just as their input needs differ. Some

columns are required on one sheet and not on another.

All sheets show the object coordinates with time: t, x, y, z as well as r, θ, φ. Distances are in metres for the Paris sheet, megametres for Satellites, and gigametres

for planets.

On the Paris, Geo, and Elliptic sheets there are also columns for:

Alt = r - earthRadius

ObjectLat = sub-point on Earth latitude of object

ObjectLon = sub-point on Earth longitude of object

Range = distance from launch sub-point and to object sub-point

as an arc distance

Bearing = azimuth angle from launch sub-point to object sub-point

measured clockwise from North.

KE-PE is kinetic energy less gravitational potential energy:

= mass * (Vx^2 + Vy^2 + Vz^2) / 2 - GM * mass / r

At escape velocity KE-PE is zero.

The Elliptic sheet has two additional output columns:

Obs Elevation is the elevation the observer sees between his horizon

and the object in orbit, in degrees.

Obs Az is the azimuth the observer sees between his north compass

point and the object in orbit, in degrees, measured in his tangent plane

Integration Routine for Macro

Overall, the macro that processes the spreadsheets is organized as follows:

Calculation()

Initialize (determine all required globals, including standard atmosphere

model)

GetInputs()

(get the configured parameters for the simulation)

OutputAnalytics()

(analytic calculation)

Integrate()

(There is a choice of employing a first or a second order integration

process. The second order process is further discussed subsequently. Both processes

include

writing individual

rows of output at prescribed intervals of the integration process)

OutputResults()

(this includes drawing charts according to output rows

derived by Integrate())

End

Apart from second order integration, the routines in the macro use straightforward spreadsheet

processes to obtain and present data. Formulas used for analytic calculations are

covered elsewhere.

The integrate subroutine is best described with psuedo-code. The syntax used corresponds

to Excel Basic:

Integrate()

' set up the initial values for variables according to configured inputs

If (ActiveSheet.Name = "Planet") Then

r = launchAlt ' the entered value is center-center

distance

Else

r = earthRadius + launchAlt

End If

Theta = Pi / 2# - launchLat

phi = 0

x = r * Sin(Theta) * Cos(phi)

y = r * Sin(Theta) * Sin(phi)

z = r * Cos(Theta)

Vr = launchVelocity * Sin(launchElev)

Vtheta = -launchVelocity * Cos(launchElev) * Cos(launchAz)

' for the Paris worksheet, the object is launched from a cannon that

is rotating

' with the earth, so imparts an additional phi velocity to the object

If (ActiveSheet.Name = "Paris") Then

Vphi = launchVelocity * Cos(launchElev) * Sin(launchAz)

+ factor * 2 * Pi * r * Cos(launchLat) / siderealDay

Else

Vphi = launchVelocity * Cos(launchElev) * Sin(launchAz)

End If

' Resolve the spherical V into Cartesian V

Vx = Vr * Sin(Theta) * Cos(phi) + Vtheta * Cos(Theta) * Cos(phi) -

Vphi * Sin(phi)

Vy = Vr * Sin(Theta) * Sin(phi) + Vtheta * Cos(Theta) * Sin(phi) +

Vphi * Cos(phi)

Vz = Vr * Cos(Theta) - Vtheta * Sin(Theta)

While (i <= lastStep)

r = Sqr(x ^ 2 + y ^ 2 + z ^ 2)

r3 = r ^ 3

Theta = thetaFromXYZ(x, y, z)

phi = phiFromXYZ(x, y, z)

If (stepsSinceLastOutput >= stepsPerOutput) Then

' each sheet has its own layout for output,

call respective subroutine

If (ActiveSheet.Name = "Paris") Then

OutputRowParis

ElseIf (ActiveSheet.Name = "Geo") Then

OutputRowGeo

ElseIf (ActiveSheet.Name = "Elliptic") Then

OutputRowElliptic

ElseIf (ActiveSheet.Name = "Planet") Then

OutputRowPlanet

End If

stepsSinceLastOutput = 0

End If

' Calculate the forces acting on the object at this time

' For the Paris sheet, the following set of equations assume the Earth

drags

' the atmosphere along totally. At earth's surface

' the atmosphere moves at the same speed as the ground, etc.

If (ActiveSheet.Name = "Paris") Then

Wr = 0

Wtheta = 0

Wphi = factor * 2# * Pi * r * Cos(launchLat) / siderealDay

Wx = Wr * Sin(Theta) * Cos(phi) + Wtheta * Cos(Theta)

* Cos(phi) - Wphi * Sin(phi)

Wy = Wr * Sin(Theta) * Sin(phi) + Wtheta * Cos(Theta)

* Sin(phi) + Wphi * Cos(phi)

Wz = Wr * Cos(Theta) - Wtheta * Sin(Theta)

Else

Wx = 0

Wy = 0

Wz = 0

End If

' total force on the projectile is sum of buoyancy, air friction,

gravity.

' buoyancy factor (BF) is radial, friction factor (F) is in opposite

' direction of velocity.

' BFr, FFv group common factors to avoid duplicate multiplications

Sy(row) = r - earthRadius

Atmosdensity ' update ph(row) for this value of Sy(row)

BFr = GM * (1 - ph(row) / Density) / r3

' radial bouyance and gravity factor

FFv = Kay / 1.225 * ph(row)

FFx = FFv * (Vx - Wx) ^ 2 * Sgn(Vx - Wx)

FFy = FFv * (Vy - Wy) ^ 2 * Sgn(Vy - Wy)

FFz = FFv * (Vz - Wz) ^ 2 * Sgn(Vz - Wz)

' get the current acceleration due to these forces

' use second order update process ie 3*Fcurrent/2 - Aprevious/2

Ax = -(BFr * x + FFx)

Ay = -(BFr * y + FFy)

Az = -(BFr * z + FFz)

x = x + 0.5 * (3 * Vx - prevVx) * delta_t

y = y + 0.5 * (3 * Vy - prevVy) * delta_t

z = z + 0.5 * (3 * Vz - prevVz) * delta_t

' done with using prevVi, so update them for next time through loop

prevVx = Vx

prevVy = Vy

prevVz = Vz

Vx = Vx + 0.5 * (3 * Ax - prevAx) * delta_t

Vy = Vy + 0.5 * (3 * Ay - prevAy) * delta_t

Vz = Vz + 0.5 * (3 * Az - prevAz) * delta_t

' done with using prevAi, so update them for next time through loop

prevAx = Ax

prevAy = Ay

prevAz = Az

' move to the next step and increment quantities accordingly

i = i + 1

' for the first set of steps, time, t = t + smaller, dynamic time

increments.

' after that, time is determined by stepSize and i (= step number)

If (i > 10) Then

t = (i - 10) * stepSize

stepsSinceLastOutput = stepsSinceLastOutput + 1

ElseIf (i > 2) Then

smallStepSize = smallStepSize * 2

t = tPrev + smallStepSize

Else

t = tPrev + smallStepSize

End If

delta_t = t - tPrev

tPrev = t

Wend

End Sub ' Integrate

Second Order Integration

Many methods have been developed for numerical integration.

Their many descriptions and applications are beyond the scope of this topic. The

reader will find many sources

of information on methods of numerical integration

in mathematical texts and on

the Internet.

How do you measure the worth of

an integration method?

When computation time is considered as important, a user would like to achieve a

desired precision while

using the least calculation time. For a given problem class some methods

will be better in this sense than others. Our 3D spreadsheet macro provides the user with

two choices, a first order process and a second order process.

The fundamental step in first order integration involves deriving a new quantity, such as

velocity, by adding to the current velocity the product of acceleration and the time interval of the step. This first order process produces better results the more slowly the involved quantities change over time and the smaller the time

interval of the step.

Second order modeling may improve the

process, especially where the quantities change with time but are well behaved, as in the motion of satellites

around the earth.

To describe second order integration more precisely, let the time varying

acceleration, velocity and position be represented by the symbols A(t), V(t), and R(t), respectively.

At any particular step in the integration, the time t = t0, V(t0) and R(t0)

are known because they are derived from the integration loop. The acceleration A(t0) is calculated from the velocity V(t0)

which in turn has been calculated from the influences of gravity, buoyancy and atmospheric

resistance on the object at position R(t0).

To obtain a second order estimate of the next value of velocity V (at time t1

= t0 + Dt where step size Dt = t1 - t0

= t0

– t-1), we approximate V(t) with the first

three terms of a power series

, around the current time, t0. This series is:

V(t) = V(t0) + C1 * (t – t0)

+ C2 * (t – t0)^2

, where C1 and C2 are constants that can to be found in the manner that follows.

Rearranging

the foregoing expression and presuming that time dt is extremely small

gives:

dV = V(t + dt ) - V(t)

= V(t0) + C1 * (t

+ dt – t0) + C2 * (t + dt – t0)^2

- V(t0) - C1 * (t – t0)

- C2 * (t – t0)^2

Then expand the squared terms to provide:

dV = V(t0) + C1 * (t + dt – t0)

+ C2 * (t^2 + dt^2+ t0^2

+2t*dt -2*t*t0 -2*dt*t0)

- V(t0) - C1 * (t – t0)

- C2 * (t^2 - 2 * t * t0

+ t0^2) then,

presuming that C2*dt^2 is so small that it can be neglected and collecting terms

obtain:

dV = C1 * dt + 2 * C2 * (t -t0)

* dt or:

A(t) = dV/dt = C1 +2 * C2 * (t – t0)

Then at t = t0:

A(t0) = C1 + 2*C2 * (t0–

t0)

That is: C1 = A(t0)

At t = t-1

A( t-1) = C1 + 2 * C2 *

( t-1– t0)

and since ( t-1– t0)

= -Dt

A( t-1) = A(t0)

- 2 * C2 * Dt = Thus:

C2 = (A(t0) - A( t-1))

/ (2*Dt

)

The velocity model is:

V(t) = V(t0) + C1 * (t – t0)

+ C2 * (t – t0)^2 that,

using the values for C1 and C2, becomes:

V(t) = V(t0) + A(t0)

* (t – t0) + (A(t0)

– A(t-1) / (2 * Dt) * (t – t0)^2

Setting t = t1 gives a second order estimate

of velocity V(t1) as:

V(t1) = V(t0)

+ A(t0) * (t1

– t0) + (A(t0)

– A(t-1)) / (2* Dt) * (t1

– t0)^2

and setting (t1

– t0) = Dt we obtain:

V(t1) = V(t0)

+ A(t0) * Dt +

(A(t0)

– A(t-1)) / 2 * Dt or:

V(t1) = V(t0)

+ ( 3 *A(t0)

– A(t-1)) * Dt /2

Which is the sought second order estimate for V(t),

Note that A(t0) must be

retained in memory

to serve as A(t-1) in

the next iteration.

We sometimes describe the process of estimating the next value as a prediction method.

Comparative Performances of First and Second Order Integration in Vacuum

In the absence of an atmosphere the period of an orbit can be determined analytically with

great accuracy. In exactly one period the xyz parameters should be identical to

those at the beginning of the period. This fact is used to compare the performance

of integration methods and step sizes.

For the comparison we chose a body in an eccentric equatorial orbit with a minimum altitude of 100,000 m and maximum altitude

of about 626,849 m. The chosen period was 5500 s.

A chart showing the xyz parameters for this orbit at t = 0, and again at t = 5500

employing 1st order integration, red, and 2nd order integration, blue, each with

three step sizes is shown next:

It can be observed that 2nd order integration with step size 0.55 s provides a more

accurate result than does a step size of 0.000055 s when 1st order integration is

employed.

Note that the derivation of a second order integration process for use when step

size is not uniform is available from the Download tab on the upper row of tabs.

As it provides a somewhat broader and more detailed view of numerical integration,

the interested viewer may wish to consult it.

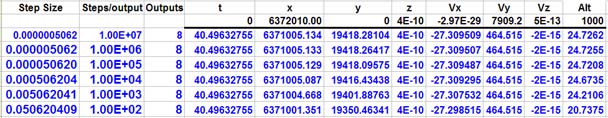

Second Order Integration in Atmosphere

There are no analytic benchmarks for trajectories in atmosphere.

One method of determining a useful step size for a class of problem is

to observe the convergence of trajectory characterization values, as step size is made

smaller. This is the procedure now illustrated.

For illustration we chose a body with a velocity that in vacuum would result in a circular equatorial Earth orbit

at an altitude of 1,000 m with period of just over 5062 seconds. In atmosphere it will be in a sub orbit and fall to the

Earth The

body was assigned a Cd of 2.0. Its xyz parameters and altitude at t = 40.49632755.... s were observed for a range of step sizes. See the results next:

The accuracy required by the user might be to about the

nearest metre in altitude. Noting that there is little and diminishing change in

reported altitude taking place when step size is below ~0.005, then that or a slightly smaller step size could be chosen.

Next

The use of a spreadsheet to find a complete orbit

from a few observations.